|

Published: 5 September 2011

Thylacines shot for sheep kills may have been innocent

New research from the University of New South Wales Computational Biomechanics Research Group has raised a tragic prospect: that in the early twentieth century the Tasmanian tiger was mistakenly blamed and hunted towards extinction for attacking sheep. In fact, its jaw’s morphology and weakness suggest the thylacine was only a hunter of native prey, no larger than a small wallaby.

|

|

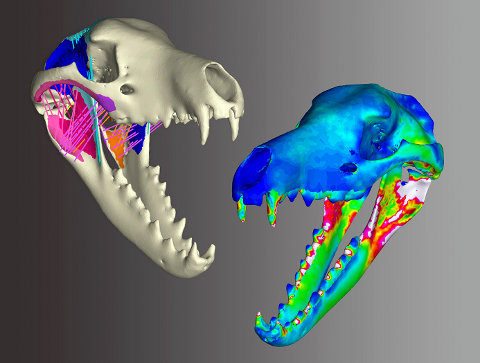

Digital stress tests reveal weakness (red/white areas in right-hand image) in the thylacine jaw. Credit: Marie Attard

|

The group’s investigation has just been published in the Zoological Society of London’s Journal of Zoology. Using advanced computer modelling to assess the design and performance of a thylacine’s jaw bones, the research team was able to simulate various predatory behaviours, including biting, tearing and pulling, to predict patterns of stress in the skull.

They then compared the results with those of Australasia’s two largest remaining marsupial carnivores, the Tasmanian devil and the spotted-tailed quoll.

This comparison showed the thylacine's skull was highly stressed compared to those of its close living relatives in response to simulations of struggling prey and bites using their jaw muscles.

Marie Attard, lead author from the Computational Biomechanics group said, ‘Our research has shown that its rather feeble jaw restricted it to catching smaller, more agile prey.

‘That's an unusual trait for a large predator like that, considering its substantial 30 kg body mass and carnivorous diet. As for its supposed ability to take prey as large as sheep, our findings suggest that its reputation was at best overblown.

‘While there is still much debate about its diet and feeding behaviour, this new insight suggests that its inability to kill large prey may have hastened it on the road to extinction.’

Director of the Computational Biomechanics Research Group, Dr Stephen Wroe, said, ‘By comparing the skull performance of the extinct thylacine with those of closely related, living species we can predict the likely body size of its prey.’

The researchers confirmed the Tasmanian tiger’s top predator status, but Dr Wrote said, ‘We can be pretty sure that thylacines were competing with other marsupial carnivores to prey on smaller mammals, such as bandicoots, wallabies and possums.

‘Especially among large predators, the more specialised a species becomes, the more vulnerable is it to extinction.

‘Just a small disturbance to the ecosystem, such as those resulting from the way European settlers altered the land, may have been enough to tip this delicately poised species over the edge.’

Thylacines once ranged across Australia and New Guinea, but were found only in Tasmania when European settlement commenced. The resulting loss of habitat and prey, and a government bounty paid to hunt them, have been blamed for the demise of the iconic species by 1936.

Source: Life Science New, Wiley